Feature

COP29: can the world reach 1.5TW of energy storage by 2030?

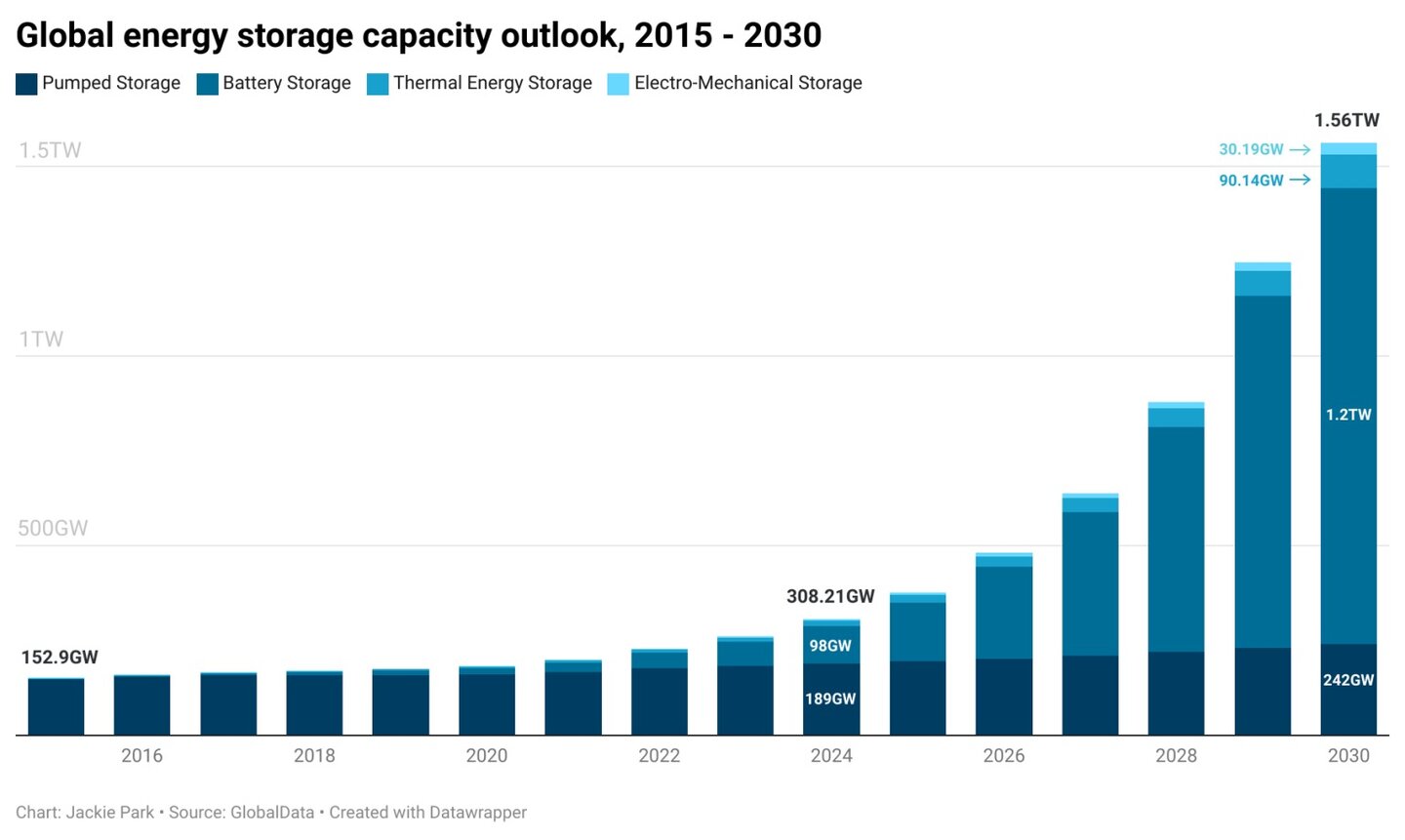

The world is on track to increase global energy storage capacity sixfold by 2030, as agreed upon at COP29, but implementation will require an update. Jackie Park and Sraddha Sabu analyse.

Energy storage systems must be deployed alongside renewables. Credit: r.classen / Shutterstock

At the annual Conference of Parties (COP) last year, a historic decision called for all member states to contribute to tripling renewable energy capacity and doubling energy efficiency by 2030.

A year later at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, the clean energy transition has accelerated with yet another decisive pledge for the power sector – one of the more significant decisions to come out of this year’s conference.

The Green Energy Storage and Grids Pledge, launched on 15 November, targets a goal of 1.5TW of global energy storage by 2030, marking a sixfold increase from 2022 levels, in addition to doubling grid investment and developing 25 million kilometres of grid infrastructure.

Several countries including Belgium, Brazil, Germany, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, the UK, the United Arab Emirates, Uruguay and the US have already committed to this pledge.

Speaking to Power Technology at COP29, Eddie Rich, CEO of the International Hydropower Association, says: “I am very pleased to see world leaders acknowledge for the first time that renewables are not just about volume but also about the mix and particularly, storage.”

Julia Souder, chair of the Global Renewables Alliance and CEO of the Long Duration Energy Storage Council (LDES), agrees, describing the new energy storage target as “desperately needed to complement the renewable energy targets of COP28”.

Nevertheless, achieving this goal in the next six years will require large-scale mobilisation of all storage technologies, which presents a range of challenges.

The road to 1.5TW by 2030

Souder believes the global energy storage market will continue to flourish, ultimately reaching the COP29 target, due mainly to its financial benefits. The LDES council’s 2024 LDES report highlighted that deploying 8TW of LDES by 2040 can save up to $540bn annually, savings that eclipse that of other alternatives to meeting net zero.

“Because [with energy storage] you won’t be curtailing all that wind and solar, you won’t waste billions of dollars. You capture all that energy and bring savings back to customers,” she says.

Rich says that the COP29 target will be “a big push” for the industry, allowing for the market to grow. “There is a good reason we set these targets. It brings political awareness and sends market signals.”

According to Power Technology’s parent company, GlobalData, global energy storage capacity is indeed set to reach the COP29 target of 1.5TW by 2030.

Upcoming hydrogen capacity by country. Source: GlobalData Energy Transition Database.

Rich explains that pumped storage hydroelectricity (PSH) has been central to the energy transition, having contributed more than 90% of deployed global energy storage capacity until 2020.

GlobalData analysis shows that PSH still leads the way, estimated to reach 189.46GW in global cumulative capacity by the end of 2024, while battery storage comes in second with 98.78GW, thermal storage 14.95GW and electro-mechanical storage 5GW.

However, PSH is likely to lose its standing as the most significant contributor to global storage capacity within the next two years.

Although pumped, thermal and electro-mechanical storage will continue to expand – set to register 241.7GW, 90.14GW and 30.19GW by 2030, respectively – the trajectory to surpassing 1.5TW owes largely to the projected exponential growth of battery storage, which is expected to register 1.2TW by 2030.

Battery energy storage systems (BESS) have seen accelerated development in recent years, with technological breakthroughs bringing costs down and compelling innovations opening doors for new storage applications.

Regardless of the rate of growth, however, Souder says that every energy storage technology will inevitably see continued expansion as each serve a specific purpose for different sectors.

The momentum of BESS across the world is driven by “appetite for battery projects on the developer and investor side”, combined with increasingly strong political will, flexible energy lead at Aurora Energy Research Eva Zimmermann explains. Sebastian Gerhard, director of batteries at Vattenfall, agrees that “every value chain step – development, production, construction and operations” – is experiencing explosive growth.

Regardless of the rate of growth, however, Souder says that every energy storage technology will inevitably see continued expansion as each serve a specific purpose for different sectors. “Every sector that is working towards decarbonisation – ports, transportation, agriculture, district heating and cooling – needs LDES, and each need a different type of storage.

“That is why we know we can meet this [1.5TW] target. We will see growth for every energy storage technology because we need different tools for different applications.”

Roadblocks remain, but opportunities to expand energy storage have “no limit”

However, energy storage deployment still faces a plethora of challenges.

“I think one of the challenges is just the lack of understanding of the benefits that LDES can provide,” Souder says. Rich adds that, “energy storage, often requiring big infrastructure, has high capital costs, but the market is not so good at knowing how much we are actually going to need for the battery, so we need to better design the market”.

He points to China and India as exemplary governments that have sent “robust market signals” for the growth of their energy storage markets. “They reward not just for turning the lights on but for providing 24/7 electricity. That means every company has to deliver not just wind or solar, but a whole mixture that guarantees 24/7 clean energy through storage, with tax subsidies, mandates and long-term visibility of revenue.”

Rich elaborates: “The first thing policymakers need to understand is that there is no limit of potential sites for energy storage. That is not going to be the problem.”

He refers to research by the Australian National University, which created a global atlas for potential off-river PSH sites and identified more than 600,000 locations worldwide. For other LDES technologies, depleted gas fields, underground caverns and industrial facilities with excess heat produced can also be repurposed to develop storage.

Souder echoes the sentiment that policymakers need to help create better markets and update policies to incorporate the value of long duration storage.

“In the UK, they realised that they have lost billions of pounds with offshore wind curtailment, so they have introduced a cap-and-floor mechanism to leverage investment in LDES. We have also seen an unprecedented number of requests for LDES proposals from various governments, like that of India and Germany,” she adds.

“So, this [governments sending market signals] is already happening. It is not brand new, which is why we feel so empowered that more of this is achievable.”

COP29 saw further industry mobilisation behind this goal. The International Hydropower Association launched the Global Alliance on Pump Storage at the summit, with 35 national government leaders and international agencies agreeing to collaborate on further development of energy storage technologies and share relevant policies and practices.

“At this year’s COP, there was growing awareness that having the nationally determined contributions incorporate LDES will be a very powerful tool for countries to deploy their different capabilities to decarbonise,” Souder says.

But she concludes stating that reaching the 1.5TW might still not be enough.

“We really need storage to make sure we maximise the entire value of renewable energy. So, even though there is a sixfold increase to 1.5TW, it really is not even enough. It is just a foundation – a starting point to get us where we need to be.”