Coal

The death of the coal supply chain?

Matthew Farmer investigates how the “artificial” market force of global warming and action against pollution has pushed the fuel onto the slag heap.

T

he end for coal seems certain. While COP26 did not achieve legal, verbal clarity on the end of all coal, future conferences almost certainly will. As the movement to cut out coal in the medium term grows, so does the fuel’s geographic divide. Most anti-coal rhetoric comes from North America and Europe, while eliminating coal seems unthinkable to Asian and Oceanian economies built on carbon.

This imbalance brings the future flow of coal into question. Existing systems cannot continue and coming years could see international coal supply chains devolve into a confusing mess. The past few years have given a taste for this, as several events have disrupted a previously unremarkable market. Coal today looks very different to coal in 2019.

For most goods, the events of recent years seem like a brief intermission in normal service. But with forces acting against coal as a whole, does the same logic apply? If the direction of travel for the most polluting fossil fuel now seems certain, how will supply chains adapt? Is disruption now the natural shape of coal?

Action on global warming changes coal prospects in an instant

Assigning an end date to domestic coal generation is currently in fashion for international geopolitics. As sister publication Energy Monitor pointed out, not all coal phase-outs have the same urgency or thoroughness. However, the direction of travel is clear.

In Europe, most countries have a small but significant coal power generation base, which they have now moved to eliminate. Massive reliance on coal made Germany and Poland Europe’s biggest supporters of the fuel, but now both have established a timetable to end this relationship.

Germany currently plans to end coal power generation by 2030, an advance on the previously-planned 2038 deadline. Imports have almost halved since 2016, according to the International Energy Agency, and production has slowly declined since 2000.

Nowadays, Poland produces 96% of coal made in the EU, with the remainder mined in Czechia. Approximately 80% of Poland’s coal coke and all of its coal briquettes stay within Europe.

Poland signed up to a COP26 deal to phase-out coal, and while the country could continue extracting coal after ending coal generation, one-fifth of its coke business relies on Germany. Almost half of coal briquette exports go to Czechia, which will end its coal generation in 2033.

/ The US remains a relative stronghold for coal, exporting approximately $11.5bn of coal in 2019. This equates to more than double the net imports of Germany in 2020. /

These changes virtually eliminate Europe’s role in the coal supply chain. Between 2000 and 2020, the EU’s coal production fell from 169 million tonnes to 56.5 million tonnes. This fall of two-thirds was roughly mirrored by the fall in coal deliveries to power plants, which fell by roughly half in the same time period.

The US remains a relative stronghold for coal, exporting approximately $11.5bn of coal in 2019. This equates to more than double the net imports of Germany in 2020, but approximately 0.75% of all US exports, according to the Observatory for Economic Complexity (OEC).

The country has not set a specific end date for coal use, as domestic politics skew any discussion of the subject into rhetoric and resource nationalism. The country has its own supplies of coal, fiercely defended by the areas surrounding them. This defence often spills over into offence, where states undermine environmental legislation to preserve existing private companies.

While US politics remain fractious and uncertain, this in-fighting has remained a largely local concern. India and Japan import the largest shares of US coal, with 16% and 13% respectively, but on their end, these imports play only a small role in the melee of trade in East and South-East Asia.

Trade disputes disrupt coal’s strongest market

Outside of trade economics, politics have altered trade between the world’s largest coal exporter and the world’s largest coal consumer. Disputes between Australia and China started in 2019, when China reportedly delayed Australian coal shipments.

A spokesperson for China’s foreign ministry told Reuters that the government had imposed restrictions to “better safeguard the legal rights of Chinese importers and to protect the environment”.

At the time, Australian ministers accepted the delays and relations remained cordial. But, as with everything else, Covid-19 changed this. In early 2021, the Australian Government called for an independent inquiry into its origins of the virus, which first came to prominence in the Chinese city of Wuhan. In response, the Chinese ruling party blocked imports of several Australian products, including barley, copper and coal.

/ Regardless of the reasons behind the trade dispute, this stopped $9.36bn in coal trade, based on 2019 estimations. /

Regardless of the reasons behind the trade dispute, this stopped $9.36bn in coal trade, based on 2019 estimations. According to the OEC, nearly half of China’s coal imports came from Australia that year. This relationship ended overnight and remains gone at time of writing. Given the industry’s direction of travel, sister publication Mining Technologybelieves that this could prove permanent.

Given the disruption caused by the pandemic, comparing trade statistics for 2020 and 2021 against other years offers few insights. However, the tangible consequences of this trade dispute became obvious later in the year.

China turns to India for supply

In September 2021, most of China experienced managed blackouts, massively affecting industry and commerce. In some areas, regional governors organised these blackouts as a way of reducing energy consumption to below nationally set targets. However, high international coal prices and the country’s reliance on coal-fired power generation certainly played a part.

To remedy the situation, Chinese authorities lifted the restrictions on coal mining enforced by the country’s national production plan. Chinese mines picked up the deficit, dropping domestic coal prices from their peak of approximately $314/tonne (CNY1800/tonne). This peak, and prices over the following months, remained significantly above international coal prices.

/ China’s embargo of Australia made it hungrier for other sources of coal, pushing international prices up further. /

China’s embargo of Australia made it hungrier for other sources of coal, pushing international prices up further. Neighbouring India stepped up production to meet the market, but India had its own coal difficulties at the time. Similar shortages meant that in October 2021, nearly 80% of India’s coal plants had less than five days of stocks remaining. Blackouts lasted hours, and 13 coal-burning plants paused generation entirely to preserve stocks for other stations.

In this case, monsoons had closed mines and suppressed coal production, hitting energy company’s small stockpiles hard. But the rapid expansion of India’s domestic coal industry makes events like this decreasingly likely. India has positioned itself to take advantage of continuing coal generation in India, and market forces have driven the country to invest further in coal.

Where will the production go?

Australia is the world’s largest coal exporter, and in October last year, the Australian Government outlined its plan to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. This came from a coalition of Australia’s least climate-motivated politicians, who seem likely to be defeated at this year’s elections.

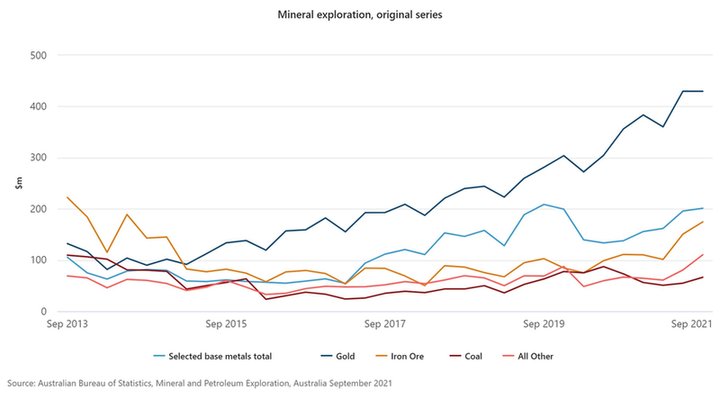

While this remains uncertain, Australia’s coal exploration has remained relatively consistent over the last decade. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, current coal exploration sits approximately 50% above the lows of 2016/17.

Although future governments may seek to suppress coal, the country also sees a level of resource nationalism that makes cutting ties difficult. Individual companies have sold coal mines and divested from the fuel, but others seem willing to take on the challenge of coal.

Just as they did when supplies ran low, both India and China will ramp up their domestic coal production. However, products will likely remain within their respective countries. Both India and China roundly defended coal use at COP26, and both have massive coal power generation bases.

/ Both India and China roundly defended coal use at COP26, and both have massive coal power generation bases. /

In China especially, many of these have already become stranded assets, unprofitable to use. Many more power stations will likely suffer the same fate, but both governments are reluctant to speed up their obsolescence.

As international coal supply chains become more unreliable, governments have lent their support to domestic industry. In some countries, this comes on a wave of resource nationalism, aiming to tie resources to national identity.

But Covid-19 has made a logical case for simplifying supply chains and keeping production local. Ultimately, the pandemic has not only damaged international trade in the short term, but also reduced confidence in its future.

Sustainability has permanently disrupted the coal trade. International shipping also has a notoriously poor environmental record, and the movement to reform regulations there has already started. Equally, the discussion of carbon borders in the EU has brought trade tariffs into the drive for sustainability.

Both would mean further disruption to international supply chains, reinforcing the business case to minimise trade and keep coal domestic.

Countries such as India and Australia will see this as unthinkable, but it comes as the logical result of their policies. Even if coal-fired power generation continues beyond 2050, international coal trade likely will not.