Feature

Navigating the challenges of transboundary hydropower

The allure of clean energy is powerful, but for countries sharing rivers, hydropower can come with a range of hidden costs. Jackie Park investigates.

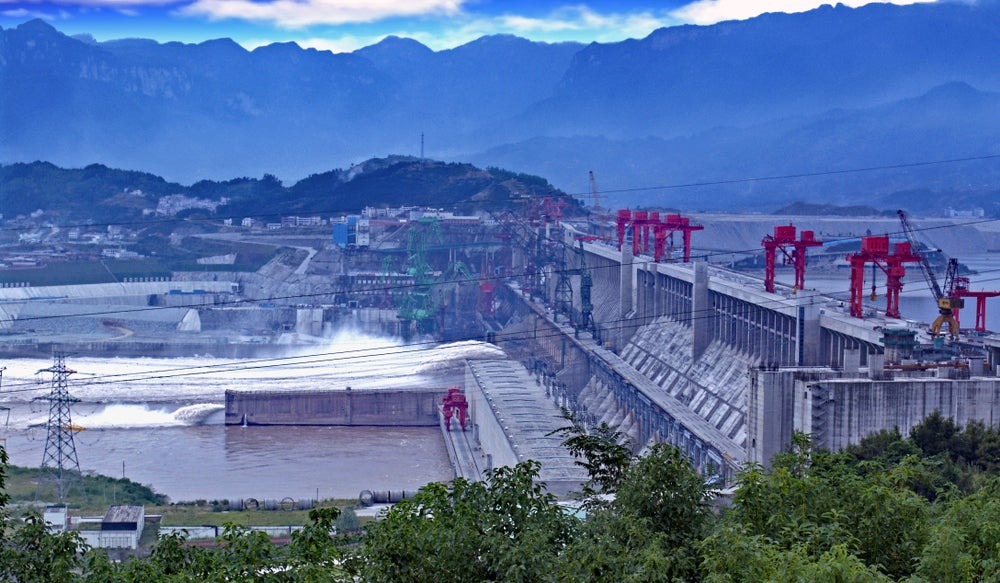

Large-scale dam projects have a history of sparking protests among environmental activists and local communities. Credit: Shutterstock

As the oldest form of renewable energy, hydropower has long been hailed as a promising green alternative to fossil fuels. However, hydropower projects on transboundary rivers have emerged as points of geopolitical tension, environmental concern and social unrest.

Nowhere is this more evident than with China’s proposed mega dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo river in Tibet (also known as the Brahmaputra river). While China celebrates its plans to build the world’s largest hydropower facility, its neighbours India and Bangladesh, as well as Tibetans themselves, fear its potential consequences.

China’s mega dam is estimated to have triple the power capacity of the current largest hydropower facility, the Three Gorges Dam (pictured above) on the Yangtze River. Credit: Thomas Barrat / Shutterstock

The risks of transboundary hydropower reveal the intricacies and conflicts inherent in the pursuit of a cleaner energy future. As the world joins hands to meet renewable targets, it is essential that potential side effects are managed to ensure a truly sustainable and equitable path forward.

China’s mega dam: a microcosm of transboundary hydropower’s potential costs

Despite hydropower’s sweeping benefits in terms of climate change and energy security, the reality of its development is more complex.

Behind hydropower’s stature as a beacon of sustainability lies sustainability risks. The same projects that can reduce carbon emissions can also exacerbate environmental degradation, such as disruption of ecosystems and deforestation, if not managed responsibly. Displacement of local populations, disruption of livelihoods and cultural erosion may also accompany large dam projects, adding a human rights dimension to the debate.

Another layer to this paradox is the uneven distribution of benefits and costs. “Urban elites tend to benefit most from hydroelectricity, while the costs are borne by others,” says Susanne Schmeier, head of the water governance department at IHE Delft Institute for Water Education. “Beyond generating clean electricity, there is also a sustainable development goal to promote electricity for all.”

More commonly, preventative measures are taken to evade – if not, significantly reduce – such casualties, solidifying the prevalent view that hydropower’s benefits outweigh costs. However, the rare but severe costs must still be addressed.

Hydropower’s risks are aggravated by projects on shared river basins as domestic laws may not adequately address the broader impacts.

“When environmental and social assessments are conducted, they typically only focus on the domestic impacts in the host country,” Schmeier explains. “This leaves other stakeholders with little information, sparking mistrust, misinformation and misunderstanding.”

Host governments will not always take into account consequences for neighbouring nations or local populations – nor are they legally required to, in many cases.

With China’s mega dam, Tibet’s colonial status further complicates matters. “There is no prior informed consent. Tibetans face barriers to decision-making over their land living under Chinese occupation,” says John Jones, advocacy manager at non-profit Free Tibet. “With expression of any grievance, Tibetans risk getting detained, imprisoned or worse,” adds Tenzin Choekyi, senior researcher at Tibet Watch.

Meanwhile, India and Bangladesh have agonised about the potential impacts of China’s upstream activities on their geology, ecology, and food and water security. The downstream nations have denounced the Chinese Government’s mega dam plan, exemplifying transboundary hydropower’s potential to spark or escalate geopolitical tensions.

“The conflict over water is embedded in a bigger picture of border disputes between China and its neighbouring countries,” Schmeier says, indicating that the mega dam is simply a flashpoint in the region’s geopolitical context. This entanglement of politics and transboundary water disputes heightens environmental and social risks, as “with no prior agreement or fraternity”, upstream nations are more willing to prioritise their own interests over any costs beyond borders.

On the other hand, it is possible that China is building the project responsibly, taking downstream countries and local communities into account. But “it is the very fact that China has not shared information that there is alarmistic reactions”, which escalate tensions, Schmeier notes, contrasting it to other basins where transparency and cooperation “prevented conflict from escalating to that extent”.

Leaks in existing transboundary water governance mechanisms

International legal frameworks like the UN Watercourses Convention help regulate shared water resources, such as enforcing due diligence obligations to not cause significant harm on neighbouring states. Basin-level treaties and organisations serve the same purpose for specific rivers. Soft laws, such as the International Hydropower Association’s industry guidelines, provide additional guidance, while institutions such as the International Court of Justice aid in dispute resolution.

While there has been a myriad of success stories from these mechanisms, they are not always effective in practice.

For one, adoption is far from universal. As participation is voluntary, many countries, including China, opt out. This creates gaps in governance, leaving downstream countries with little recourse to address their concerns through international legal channels, Schmeier explains.

Even when all relevant countries are signatories, power imbalances can corrupt decision-making processes. Upstream nations often hold more political leverage, leaving downstream countries vulnerable with limited negotiation power.

Another shortcoming is the exclusion of local communities in decision-making processes. “There is an unequal access to knowledge, even before inaccessibly to decision-making,” Choekyi remarks, noting potential language and cost barriers that may hinder communities from participation, even when opportunities for involvement are present.

These flaws are further exacerbated by current frameworks, especially in the absence of basin-specific mechanisms, failing to account for the unique political, geographic and ecological complexities of different river basins.

“International law application is simpler for smaller basins with two, maybe three, countries involved than larger ones,” notes Ana Maria Daza Vargas, senior lecturer in international investment and water law at University of Edinburgh Law School.

In many instances, investors and upstream countries negotiate deals that directly impact downstream nations and local communities, yet there is little to no obligation to consult them. Daza Vargas attributes this to the disconnect between international water law and other legal spheres. Foreign investors and developers are typically only required to meet international investment laws and domestic laws, bypassing international human rights and environmental protection regulations.

With so many actors involved, who should be held accountable?

“To a big extent, foreign investors are dependent on the information received from the host state,” says Daza Vargas. “For domestic projects, operators handle checks, like environmental impact assessments. For transboundary projects, the host country often does.”

Developers are in the same boat. “We only know [information] we have been provided,” says a civil engineer with more than 30 years of experience in constructing hydropower projects. “Being pressed to design a project that accommodates everything when we haven’t been told everything, then blamed when we can’t, isn’t fair to engineers.”

Schmeier summarises: “Cooperation is more common than conflict with transboundary hydropower projects, but conflict arises when there are no or weak mechanisms in place.”

Dam the tensions: preventing and minimising risks

First and foremost, upstream countries must prioritise open dialogue and collaboration with all relevant parties early on to avoid problems down the line. Schmeier refers to the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), where opposition from Egypt, Sudan and Somalia – sparked by lack of communication during planning – wound up impacting Ethiopia’s economy and political stability.

Taking preventative measures, such as providing prior notification and conducting transboundary impact assessments, “reduces the surprise effect, which we know from conflict research also reduces mistrust and conflict”, Schmeier says.

Although moving beyond sovereignty will be a difficult shift, as “across the world, political thinking has gotten increasingly short-term and unilateral”, she stresses that upstream nations must recognise that “the benefits generated from cooperation in early stages far outweigh conflict”.

Legal frameworks tailored to specific river basins can optimise solutions, while stronger oversight from international bodies could help ensure nations do not act unilaterally to the detriment of their neighbours.

Schmeier explains that international institutions and frameworks “won’t have all the answers”, as demonstrated with “downstream countries accusing the Mekong River Commission (MRC) of being too pro-upstream, and upstream countries arguing vice versa”. Nevertheless, “there was a platform for countries to collaborate and exchange information, and that itself made a huge difference, compared with conflicts that emerged with the GERD or Tajikistan’s Rogun Dam, where there were no platforms at all”. In other words, having an imperfect mechanism is better than an absence of one altogether.

When all else fails, Jones suggests that “regional alliances” could also help empower downstream nations.

To ensure local communities are heard, Schmeier says one method is mandating stakeholder consultation forums, as is the case in Europe under the Water Framework Directive. The MRC also saw member countries engage with civil society actors, “albeit to different degrees, depending on each country’s political system”.

She notes, however, that “we must keep in mind that basin organisations are interstate organisations… so, if a member state doesn’t want communities to have a say, there is little the organisation can do”.

Developing greater crossover among various international legal spheres can also help ensure that downstream countries and local communities hold relevant actors accountable for the broader environmental and social impacts of transboundary projects. However, even without a formal coupling, Daza Vargas asserts that foreign investors and developers should take steps to ensure that they do not indirectly contribute to the violation of international legal norms that the host state might have – intentionally or not – neglected.

Charting the course

Although we are yet to see how China’s mega dam project unfolds, a law professor specialising in transboundary water resources at a Chinese university says that he is hopeful about the prospects for increased cooperation. He cites recent cases in which China cooperated with Kazakhstan and the MRC on shared water resources, which were “a bit different [in political context]” but indicate “positive movement”.

The potential costs of transboundary hydropower indicate that the road to a cleaner energy future is not so smooth. The global push for renewable energy needs to be balanced with environmental and social justice, raising questions about how to pursue the energy transition responsibly.

“Especially with recent warming relations between China and India”, he believes they can come to an agreement on information sharing, prior notification and consultation, and “in the best-case scenario, although unlikely, a joint management and benefit framework”.

As for Tibetans, the outlook feels bleaker. With many Tibetans stateless and their government in exile, they will continue struggling for inclusion in decision-making processes, says Choekyi, requesting support from international institutions.

Schmeier responds: “International organisations stepping in can be a double-edged sword.” While she confirms that they have a role to play in empowering civil society engagement in non-democratic states, “there is a safety concern, as past protests by Tibetan communities against dams have been met with violent crackdowns by the Chinese Government, and outside intervention may fuel these types of events”.

The potential costs of transboundary hydropower indicate that the road to a cleaner energy future is not so smooth. The global push for renewable energy needs to be balanced with environmental and social justice, raising questions about how to pursue the energy transition responsibly.

“Just because hydropower contributes to the world’s pivot to clean energy, doesn’t mean we should just ignore its potential costs,” Daza Vargas concludes.